How alumni from tiny Emerson college infiltrated pro basketball's front offices

"East Boston High," he says, starting a list. One after another, he keeps adding to it, rattling off the names of nearby schools with gymnasiums: "Simmons College, Mount Ida, Mass College of Arts, Tobin Community Center, Don Bosco High School." He finally pauses. "Umm," he racks his brain for more, then starts listing again, "Chinatown YMCA, Emmanuel College, Suffolk University." His voice is coarse, like someone who yells too much. "I'm trying to think of all the ones," he says, struggling to remember the places the school's basketball team called home. He almost immediately snags another from his memory as he lets out a quick, nostalgic laugh that's almost a sigh and says, "Boston Latin High School. The first and only time I've ever been there is for a home game about 10 years ago."

That's when Shawn McCullion, a college scout for the Orlando Magic since 2012, was an assistant basketball coach at Emerson College, a small Division III school located in the heart of Boston. Until 2006, the school had no gym. The team hopscotched around Boston and its suburbs claiming gym after gym as their home, whether for one game or many.

"I had to MapQuest a home game once," McCullion says. He was getting ready to head to Emerson to pile into vans with his team and drive to the Chinatown YMCA. Then, 10 minutes before he was set to leave his house, he learned the Y staff had ripped out all the bleachers leaving no place for the fans to sit. They had to find somewhere else to play. Fortunately, East Boston High School was available. Unfortunately, McCullion had no idea how to get there.

"This is a place I have never been to in my entire life and that was a home game for a college basketball team," McCullion says incredulously. But MapQuest came through and Emerson made the game.

Not that many fans did. The YMCA sans bleachers probably would have been fine.

Emerson isn't exactly a sports powerhouse. The school, with a combined enrollment of less than 4,500 students, is in Boston's Theater district, just off the Boston Common. For a school that touts itself as "the nation's premiere institution in higher education devoted to communication and the arts in a liberal arts context," it's the perfect location. Notable alum include former "Tonight Show" host, Jay Leno (1973), "Happy Days" star Henry Winkler (1967), actor and comedian Denis Leary (1979), Maria Menounos (2000), the host of "Extra," and numerous journalists, authors and film and television producers.

The Boston school somehow became a breeding ground for NBA front office positions.

Shawn McCullion, now a scout for the Magic, coaches on the sidelines at Emerson. (Photo credit Pete Keeling)

Shawn McCullion, now a scout for the Magic, coaches on the sidelines at Emerson. (Photo credit Pete Keeling)

A great place, unless, of course, you're interested in being a sports star. "The most popular sport on campus now is Quidditch," says McCullion. He isn't kidding.

Still, a small group of Emerson alumni has been nearly as successful in professional basketball as those from far more recognizable schools, like Duke or Kentucky. No, the Emerson guys didn't become NBA stars like Grant Hill or John Wall, but they still made it to the NBA. Over the past 15 years the Boston school somehow became a breeding ground for NBA front office positions.

Before he became a coach, McCullion, a Nashua, N.H., native who played a total of seven minutes of high school ball, played for Emerson, transferring after playing junior varsity basketball at Plymouth State College in New Hampshire.

It was the fall of 1994 and McCullion only went to the athletic department because he wanted to try out for the golf team. In the middle of the room was a banquet table with sign-up sheets for each sport. "That was how they were recruiting at Emerson at the time," McCullion says.

The basketball sign-up sheet was right next to "Golf." The athletic director talked him into signing up; there was a new coach and he needed players, even those with only seven minutes of high school experience.

Midway through the first official practice, McCullion rethought his decision to play. The team hadn't stopped sprinting all practice, it seemed, and in the middle of their fifth or sixth "minute drill," racing the length of the court time and time again, McCullion bolted. He went straight to the shower stall at the Mass College of Art gymnasium, dropped to his hands and knees and started throwing up. Assistant coach Bruce Seals, who had played three seasons with the Seattle SuperSonics in the 1970s, followed McCullion into the showers. He stood over him, took off his glasses and said, "I feel ya, young fella. I feel ya, young fella."

The new coach, Hank Smith, was unlike any McCullion had ever experienced. Smith decided that what Emerson lacked in talent, they would make up with conditioning. McCullion wanted to quit — he thought about it the entire night after that hellish first practice — but he didn't want to leave the team shorthanded, so he kept on showing up.

The running and running and running worked. The kids with no home gym could play. In the previous five seasons, Emerson had won a total of only 21 games. In Smith's first season, they won 17. In McCullion's senior year, Emerson won the Great Northeast Athletic Conference championship.

Today, as a college scout for the Orlando Magic, McCullion is responsible in part for the club's selection of players like shooting guard Victor Oladipo, an emerging star. None of it would have happened if not for Smith. He says the day he didn't quit the team was, "Without question the most important day of my life."

One day last year he was sitting in Steve Wojciechowski's office discussing NBA prospects. Wojciechowski, recently named head coach at Marquette, was then the associate head coach at Duke, second in command to Mike Krzyzewski, one of the most successful coaches in the history of college basketball. The conversation turned to Hank Smith, whom Wojciechowski had once met. Wojciechowski said, "Coach Smith is a pretty good coach I heard."

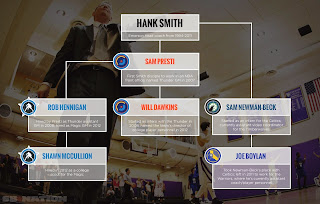

"Let me put it in perspective," McCullion said. "There's only two people walking the face of the earth that have coached two general managers in the NBA. One of them is Hank Smith. The other one's the guy upstairs. (Krzyzewski.)"

That says something.

***

The NCAA says something, too, highlighted on its Facebook page: "There are over 450,000 NCAA student-athletes, and just about every one of them will go pro in something other than sports." It's true. The odds of making an NBA roster are mind-bogglingly slim. And the odds of becoming the general manager of an NBA team are even more preposterous.

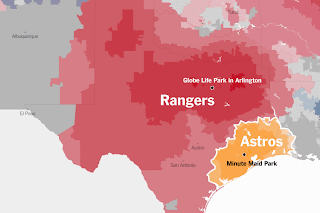

Yet two Emerson alums have done just that: Sam Presti, Class of 2000, is the general manager of the Oklahoma City Thunder and Rob Hennigan, Class of '04 is the Orlando Magic's GM. In the entire history of the NBA, only two colleges other than Duke and Emerson — UCLA and Wheaton College — have claimed two NBA GMs at the same time.

But that's not all. Four more Emerson alums are working in basketball operations for NBA teams and may one day move up. In addition to McCullion, Will Dawkins is the director of college player personnel for the Thunder, Joe Boylan works for Golden State as assistant coach/player personnel (Note: Boylan is the author's cousin), and Sam Newman-Beck is an assistant video coordinator for the Minnesota Timberwolves. Somehow, Hank Smith took a small art school in Boston and created a feeder school for the NBA. It's as if alumni from the University of Kentucky basketball program under John Calipari started winning Oscars and Pulitzer Prizes.

Smith's coaching résumé may not compare to Krzyzewski or Calipari's, but his influence in professional basketball might be longer lasting than either man's. But just as it has become visible, the Emerson pipeline may be done.

Hank Smith doesn't coach anymore.

***

Smith, who is married with two grown children, graduated from Brighton High School in Boston in 1974. Despite the presence of the champion Celtics, the city was hardly a basketball hotbed — Boston was a hockey town. But not to Smith. He was all basketball until a knee injury derailed his playing career. He didn't go straight to college. Instead, he got a job as an operations manager at an office supply wholesaler. But that didn't keep him away from the game. A gym rat, he coached youth teams at the West End Boys Club and semi-pro teams all around New England. Dennis Richey, one of Smith's best friends growing up, refers to the teams as "AAU teams before there were AAU teams." Smith just had to be near a basketball court. "I wasn't getting paid or anything," he says, "I just coached to coach."

He took his first paid coaching job in 1988 as the freshman coach at Dedham High School in Dedham, Mass. Three years later, he moved to Framingham State College in Framingham, Mass. There he realized that if he wanted to coach at the collegiate level, he was going to need a degree, so he enrolled in classes, eventually earning a bachelor's degree at Franklin Pierce College.

Smith was tireless when it came to his team. Jim Todd, who has served on the coaching staff for five NBA teams, most recently the New York Knicks, once coached at Salem State College and remembers constantly seeing Smith on the recruiting trail at high school and AAU games. "Every time I went out to a game," Todd says, "he was there." So Todd hired him on at Salem State in 1993. He says Smith was knowledgeable of the game in an "X's and O's sense," but he was also "relatable," a perfect fit for a college coach who was going to have to work with young kids.

He prepared them the only way he knew: by running them ragged.

Hank Smith coaches his players. (Photo credit Pete Keeling)

Hank Smith coaches his players. (Photo credit Pete Keeling)

After a year under Todd, Smith took the head coaching job at Emerson. He turned the program around almost instantly, insisting his team played hard and pressing in every single game. He prepared them the only way he knew: by running them ragged.

It started with the minute drill: Sprint from one end of the court to the other. Then go back. Do it again, down and back. And again. One more time. Then one last time. Ten length of the court sprints (five down and five back) in 60 seconds, the cornerstone of Hank Smith's coaching method. If anyone didn't finish all five down-and-backs in 60 seconds the entire team would run them again. The same was true if they missed the end line. Add in defensive slides, backboard touches, pushups and bear crawls, and practice was one constant conditioning session.

"It doesn't sound that bad when you write it out," says Ben Chase, who played for Emerson from 2004 to 2008 and is now the assistant coach of Houston Baptist University's women's basketball team, "but it was brutal."

In Chase's first year, before any official practices, the players met for captain's practices and were introduced to the minute drill and every other exercise they would face in practice playing on an outdoor, asphalt court in the Back Bay Fens, near Fenway Park.

Still, playing pick-up games in frigid weather and running sprints while wearing mittens to fend off the cold barely left them prepared for what was to come. The players dubbed the first week of practice under Smith, "Hell Week," rising at 5:45 a.m., piling into vans for a 40-minute drive to the gym at Pine Manor College, then practicing until 9 a.m. The rest of the year wasn't much easier.

Alex Tse, a member of Smith's first Emerson team, started the year at 150 pounds. When he hopped on the scale at the end of the season, it read 135. Tse doesn't work for an NBA team, but he's yet another successful Emerson basketball alum: He's a screenwriter in Hollywood, co-writing the 2009 film, Watchmen. He named his production company Minute Drill Productions.

Smith's coaching style didn't make it any easier. A yeller, Smith barked instructions at his team almost non-stop, his nasally voice echoing across the gym alongside the squeaking sneakers and heavy exhales bellowing from exhausted players. And on the sideline during games, Smith was equally demonstrative. He almost always scowled. He wore glasses, but the clear lenses only seemed to magnify the intensity in his eyes. It was D-III basketball coached as if it was the NBA Finals.

Roger Crosley was the coordinator of athletic operations at Emerson from 2003 to 2011. He laughs and says that a lot of the stuff Smith used to yell probably couldn't be printed. "For someone that had as crazy a sideline demeanor as he did, he got amazingly few technicals," Crosley says. "That game had 100 percent of his focus. He never thought about anyone or anything else other than coaching that basketball game."

Yet Smith was no Bobby Knight, ruling by intimidation and fear, breaking players down to build them back up and not worrying about the castoffs who couldn't cut it, able to cherry-pick replacements from among 5-star recruits. At Emerson, he primarily worked with what he had, semi-skilled players who sometimes thought of themselves as actors and poets.

Smith yelled, but he also cared deeply about his athletes. And his players loved it. For many, who had grown up in the soft embrace of the suburbs, learning to push themselves beyond what they thought they were capable of was a transformative experience.

"Coach was pretty dynamic," says Newman-Beck, who graduated from Emerson in 2009 and is now an assistant video coordinator with the Timberwolves. "He looked a little crazy at times. But you could tell he really cared about you. He just had a unique ability to get the most out of us."

He got the most out of them by not only yelling instructions, but also by being a friend. A lot of coaches can be off-putting by yelling, but the Emerson players knew Smith wanted the best for them. Plus, they had fun.

"He's incredibly passionate and a tireless worker, and prepares ad nauseam for his upcoming game or practice," says Hennigan, the general manager of the Magic. "But at the same time he doesn't take himself too seriously and he has an ability to create an interpersonal bond with you because he likes to joke around, he likes to bust balls."

Rob Hennigan, who became general manager of the Magic at age 30 in 2012. (Photo credit Getty Images)

Rob Hennigan, who became general manager of the Magic at age 30 in 2012. (Photo credit Getty Images)

***

"I think the thing about Emerson teams and the family that we have," Smith says, "is that we never try to put anyone bigger than anybody else."

In his first home game as Emerson coach, he benched the starting point guard because he was five minutes late for a practice. Tse, who says he would have been cut from most college basketball teams, started in his place. No matter the talent level, Smith would find each player a role. Tse compares it to the way hyperactive guard Randy Brown found playing time on the Bulls championship teams in the '90s.

It is fitting that many Emerson teams practiced on outdoor courts in Boston, that's where Smith honed his skills and philosophy as well. His approach was shaped while growing up in Boston in the 1960s and '70s watching greats like Red Auerbach and Bill Russell's Celtics dominate the NBA.

Ringer Park off Commonwealth Ave., in Allston, a working-class neighborhood flanked by Boston University and Boston College, was where many young, crazed Celtics fans lived out their basketball fantasies in Smith's younger years. "He was good," says Richey, who grew up playing basketball with Smith, "a very cerebral basketball player." Richey was three years behind Smith at Brighton High, so they were never on the school's team at the same time, but they played at Ringer Park constantly. BC and BU players would sometimes even show up for pick-up games. It was a cutthroat atmosphere: To keep the court you had to win. "It was a battle," Richey says, sighing, "Everything was a battle." Smith never wanted to leave that court.

He was intense, competitive, unforgiving. His players reveled in it.

As his competitiveness mounted on the playground, so did his knowledge and understanding of the game. Richey played for him on a team sponsored by Bromfield Pens in the late-'70s and early-'80s.

In one of his first adult coaching jobs, Smith was already a spitting image of his future self. "Always very intense," Richey says of Smith on the sideline back then. "Very competitive, very intense. Always wanting to do things the right way. With Hank there's a right way and a wrong way, no gray area, no in between."

Many coaches learn from the coaches they grew up with, but Smith was mostly self-taught. Richey says he and Smith didn't have any good coaches growing up: "We watched a lot of basketball, we played a lot of basketball, we kind of learned on the fly, and he was at the forefront of our group with that."

He carried his belief of right and wrong to every coaching stop he had. Once he had his own program at Emerson, he could impart those lessons he learned through the game of basketball on his players. He was intense, competitive, unforgiving. His players reveled in it, especially those who went on to the NBA.

"I don't so much call it an 'It factor,'" Hank Smith says of the six Emerson alums working in NBA front offices, "I just know that with every one of them, number one, they're all very intelligent."

Second, says Smith, is that they were willing to accept responsibility; they were very mature. He credits their families for that.

Third, Smith says, "They were always willing to do more and more for their team."

Smith may credit his players, but his players credit Smith, arguing that he prepared them for any type of job and is the biggest reason they've been successful in the NBA. At Emerson, they learned that no amount of work was too much, that talent wasn't everything, that effort and teamwork and playing smart mattered more.

Under Smith, basketball was demystified. They learned a workmanlike approach to the game, and now, in the NBA, they treat it like any other job. They aren't in awe. They are smart, creative guys — they went to an art school, after all — but smart creative guys who also have drive. Presti, for instance, is part of a new generation of NBA GM's who have embraced analytics — he's spoken at MIT's Sloan Sports Analytics Conference, appearing with Bill James on a panel discussing personnel decisions. ESPN's Bill Simmons even called him "a cool-ass nerd who reads blogs."

Whatever works.

Sam Presti, who has served as the Thunder general manager since 2007. (Photo credit Getty Images)

Sam Presti, who has served as the Thunder general manager since 2007. (Photo credit Getty Images)

***

The job of an NBA general manager is to put together a team, not just to assemble talent, but also to find a group of players and coaches that gel. A general manager needs to be able to see the team as a whole, dispassionately, yet also a group that can work together passionately. The same goes for a coach or a video intern. To work in the front office of an NBA team, all pieces of the puzzle need to be assembled and put together.

"Look at yourself honestly and understand really where you fit within the team concept," Presti says when looking at the lessons Smith imparted on him. "Really give yourself up for the collective good." He isn't giving away the tricks of the trade to how he puts together the Thunder roster — there is much more to it than that — but it's not a bad starting point. "Understanding that the collective group is the most important thing," he adds, "really forcing yourself to be a critical self-evaluator and an honest self-evaluator. I think those are really important qualities regardless of what line of work you got in to."

Players who donned the Emerson jersey under Smith learned to accept their role on the team. Smith says, "How do you maximize everybody and then cover the weaknesses everyone has?" That was his approach, and his players have taken that forward.

Presti was the first. With his stylish glasses and close-cropped, reddish hair, the lean Presti looks more like a CEO of a startup than an NBA executive. He is calculating when he speaks, careful to say the right thing, and tries to maximize his team in any way he can. He has tweaked the Thunder countless times in his effort to build a champion. They made the NBA Finals in 2012 and even after trading James Harden for contractual reasons, the Thunder have adjusted. With Kevin Durant and Russell Westbrook, the Thunder remain a serious threat to make the 2014 Finals as well.

"There was a seriousness to Sam that was different from any college kid," Tse says of Presti. He remembers that Presti hit the game-winning free throws in one of his first games with Emerson. Tse recalls being pumped and saying something to get Presti jacked up, but, as Tse says, "Sam was just matter of fact about it and described why he was prepared for that moment." Tse laughs, and keeps going, "And I was like, 'OK, this dude's serious.'"

After he graduated from Emerson in 2000, he attended a camp in Colorado where he met San Antonio Spurs basketball chief R.C. Buford. As Buford refereed a scrimmage, Presti, hyper focused, begged for an internship. It worked. He got the internship. Subsequently, he worked his way up the ladder with the Spurs to become assistant general manager — it helped that Presti, at age 24, persuaded Spurs coach Gregg Popovich to take a closer look at Tony Parker in the 2001 draft after seeing footage of Parker playing in France. He was with the Spurs for their NBA titles in 2003, '05, and '07. Then he left for Seattle to take over as general manager. He was 30 years old.

The SuperSonics left Seattle for Oklahoma City in 2008 and became the Thunder. That same year, Presti hired another Emerson alum, Rob Hennigan as his assistant general manager. "I owe everything to Sam," Hennigan says. "He's the one that gave me that chance and he's the one I was able to learn from all these years."

With Hennigan and Presti in the league, the pipeline from Emerson to the NBA was in place.

Sam Presti (Photo credit Getty Images)

Sam Presti (Photo credit Getty Images)

Hennigan followed a path similar to Presti's. After Emerson, where he was the all-time leading scorer, he took lessons from Coach Smith and applied them to his career. He began as an intern with the Spurs in 2004, choosing that position over a low-paying TV reporter's position in Alaska — before joining the Thunder. Then, in 2012, Hennigan moved on, at age 30, taking the general manager position with Orlando, where he has entirely turned over the roster, freeing them from onerous financial constraints and setting them up for the future. Emerson College not only produced two general managers, but two of the youngest GMs in the history of the league.

With Hennigan and Presti in the league, the pipeline from Emerson to the NBA was in place. More and more of Smith's players looked toward basketball as a career. Dawkins, Newman-Beck and Boylan were all on Emerson's 2007-08 team that had only one player taller than 6'4 yet still finished 15-3 in the GNAC. Over the next three years, building on the reputations of Presti and Hennigan, each scored a job in NBA.

Dawkins accepted a front office internship with Oklahoma City in 2008. Newman-Beck got his start with a video internship with the Boston Celtics before joining Minnesota as assistant video coordinator, where he still works, watching footage of Ricky Rubio doing unthinkable things with the basketball.

Boylan took a more circuitous route. The only Emerson player in the NBA not from New England, Boylan transferred to Colorado College after his freshman season. He immediately knew he made a mistake. He went back to Emerson — and Smith — just a semester later. "Before he left he was a really smart, confident guy who talked a big game, but there was something missing," Chase says. "When he came back, he was totally focused. When he came back he was a leader." After graduation, he worked with Tim Grover, a personal trainer famed for working with Michael Jordan, and in 2009, he got into coaching, working with the Portland Red Claws in Maine. When Newman-Beck left the Celtics for the Timberwolves, Boylan took his place, and then moved cross-country in 2011 to work for Golden State as video coordinator. He's still there, only now he's assistant coach/director of player personnel. Boylan, who resembles Celtics head coach Brad Stephens, sits one row behind the bench. During Warrior games, his head pops up after each play to get a better look at the court like he's part of a Whac-A-Mole arcade game.

Many coaches have a "coaching tree," people who have played or coached under them and are now at different schools. Krzyzewski's includes Tommy Amaker at Harvard, Mike Brey at Notre Dame and Johnny Dawkins at Stanford. Tom Izzo's includes Tom Crean at Indiana and Stan Heath at South Florida.

Former Knicks assistant Jim Todd sees something similar with Smith and his progeny. He likes to tease Smith, saying, "It's not the coaching tree for you, it's the manager tree."

Before 1995, Emerson basketball was an afterthought. By 2010, with five alums already in the league, there was something about this small art school in Boston.

And everyone says it's because of Coach Hank Smith.

***

There is, however, one person who does not credit Smith. And that is Hank Smith himself.

In an age where college coaches are often bigger than the teams themselves (thank the one-and-done system making the coach a much more stable face of a university), Hank Smith is nearly invisible, appearing for an interview about Presti or Hennigan every once in a while, but almost never speaking about himself. He is the embodiment of the athletes he coached. He stays out of the limelight. During all his years at Emerson, neither the Boston Globe nor the Boston Herald even saw fit to profile one of the most successful coaches in the city. He just keeps his head down and works his butt off. He is the anti-Calipari.

His former players are much the same. Presti credits Smith with his rise in the NBA. Hennigan says it's because of Presti and Smith. They all pass the buck along to someone else. And for everyone but Smith, it's Smith. "I don't want to make it out like I made them like this," he says.

But when asked about Smith, his players, from Presti the GM to Tse the screenwriter, all say versions of the same thing. It's not so much the X's and O's they learned from Smith, but the answer to a question.

"What makes you a man?" Smith always used to ask.

"My description of a man is someone who accepts responsibility," he says. "As long as you're here you are going to accept responsibility for everything you do that involves our team in any form." Smith became a man on the Ringer Park courts. He became a man while working a full-time job and still finding time to coach the boys' club and every semi-professional team he could find.

To the players he coached, learning to be a man means the same thing to all of them: take responsibility, don't make excuses.

The story of how current Suns general manager Ryan McDonough became assistant GM of the Celtics at just 33 years-old, helping to usher in a new age of player evaluation.

The players did exactly that at Emerson, where they didn't have a home court until 2006 and where they had to wash their own gold and purple uniforms, sometimes practice in a playground and play knockout for a pair of socks. They claim that's why they were successful. Not only in places like Hollywood, where Emerson grads are supposed to pop up, but the NBA, where they aren't.

Finishing four years under Hank Smith was like passing through a crucible. The alums have an understanding. Tse says, "If you can play four years and you can finish your time with him, you've passed one rung of the background check."

"The ones that bought into Smith," says Crosley, "boy, I have never seen a group of more committed individuals than Emerson's basketball players."

He remembers that after the last game of each season, Smith would keep his players in the locker room. The seniors were given a chance to talk. He wanted them to impart what Emerson basketball meant to them, what it should mean to the underclassmen. The final team meeting of the season, and for some players, their careers, would last three to four hours.

"Every cliché about a sports team," Alex Tse says, "'here are the lessons in life you're gonna learn.' Ninety percent of the sports teams, you're not gonna get that shit. They preach it, but it doesn't happen. Here, it was real."

"[Coach Smith] was always emphasizing the reflection of basketball and real life," Boylan says. "So much of it was what they say college athletics is all about, developing skills and determination. Being able to take, take, take, take and just keep on fighting with a smile on your face and then ultimately getting rewarded."

Not that it always worked that way.

In January 2011, Smith was abruptly fired as Emerson's head coach. Although the athletic department announced that he decided to leave, William P. Gilligan, the vice president of information technology who oversaw athletics told the Berkeley Beacon, Emerson's school paper, "the decision was made by the College to no longer, in essence, to no longer have Mr. Smith as the coach."

Just like that, Hank Smith was gone as coach at Emerson.

No one will really talk about what happened. Certainly not Smith. But at art-oriented Emerson, a coach like Smith was, increasingly, an anachronism, old school, perhaps not quite the image the school wanted to continue to put forward.

The team's alumni network didn't take it kindly, and the relationship between the Emerson basketball family and the school is still tense. McCullion says, "I don't really feel like I have an alma mater."

"Hank was a good coach," says Crosley. "He had players that loved him, he loved his players ... He was a winning coach. He didn't cheat. His sideline antics could be a little entertaining at times, but he wasn't Bobby Knight throwing chairs across the floor. He was a good coach and a good man and he deserved a better fate at Emerson."

All Smith will say is this: "I was really luckier than they were."

"All those people, all the good things they brought to me was incredible."

***

Emerson has a gym now. It's three stories underground at 150 Boylston, next door to an M. Steiner & Sons piano store, just off Boston Common.

There's a small plaque next to the elevators in the lobby. In 2006, at one of Emerson's first home games in their gym — the gym that many Emerson alums never had — the Emerson basketball family gathered in that lobby after the contest, standing before a flimsy, black drape hanging on the wall.

McCullion addressed the small crowd. He told a story about Coach Smith calling him in 2000 to tell him Presti was going to be an intern with the Spurs. He said that Coach guaranteed Presti would be a general manager some day. "The first day Sam got the internship, Coach knew that he was going to be a general manager," McCullion said. "And after that, whenever he said anything, I really listened." Everyone laughed. McCullion told everyone that Hennigan was next. Then he pointed to Dawkins and Boylan. Coach Smith had given them a stamp of approval, and even then, McCullion knew they were going to be big.

Then he peeled away the drape and revealed a plaque that reads:

In honor of

Coach Hank Smith and family

-gift of your players

to whom you have dedicated so much

2006

The plaque is still there, one of the few reminders of Hank Smith's time at Emerson, but the alums just don't feel like it's home. They were fine without a home gym before, they'll be fine again. They've accepted responsibility, there's nothing they can do about it now.

Besides, there's another sign of Smith's accomplishment, and that of the young men he coached. It's not just in the front offices of the NBA, or on the court, where players who Hank Smith would have loved to coach have been picked out by some of the men he did to play a role, and find a place, on a team in the NBA.

It's also in the stands, where one more Emerson alum is employed in the NBA now. Smith is Emerson's de facto seventh NBA staffer. He works for Presti and the Thunder as a special assignment scout.

And if you know where to look, you can sometimes find him sitting in the stands of a gym somewhere, maybe in the NBA, maybe in some small, out of the way college, some place where you might not expect to find an NBA scout. He's the guy watching intently, taking notes, looking for the kid who will come back into the gym after the minute drill has made him ill, a man among all the boys.