Monday, December 22, 2014

Thursday, November 6, 2014

Wednesday, November 5, 2014

NPR Story

http://www.npr.org/blogs/alltechconsidered/2014/11/04/360430620/from-silicon-valley-to-white-house-new-u-s-tech-chief-makes-change

http://www.npr.org/2014/10/14/353525565/for-lapd-cop-working-skid-row-theres-always-hope

Tuesday, September 23, 2014

NFL

http://espn.go.com/blog/boston/new-england-patriots

Tuesday, August 19, 2014

Wednesday, July 2, 2014

Boston Globe Article

Why is the American story of nature and conservation so white? Carolyn Finney uncovers a complicated history.

By Francie Latour

| June 20, 2014

Mladen Antonov/AFP/Getty Images

The Giant Sequoia at Sequoia National Park in California.

Each year, California's Sequoia National Park draws a million people to commune with nature and be dwarfed by some of the largest living things on earth. Visitors pass trees recognizing presidents and heroes of war: Washington, Sherman, Lincoln, Grant. A summit trail bears the name of John Muir, known as the father of our national parks.

But few Americans know the name or story of the man who carved this national park into being: Charles Young, a black Army Captain born into slavery in Mays Lick, Ky. It was Young, with his segregated company and crosscut saws, who transformed Sequoia from an impenetrable wilderness to a tourist mecca. In 1903, with teams of mules hitched to wagons, Young's mountaineers became the first to enter the Giant Forest on four wheels.

When we think of great conservationists, or just ordinary Americans trekking in the outdoors, we don't typically picture black faces. There are reasons for that: Today, more than a century since Young's team opened up Sequoia National Park, blacks are still far less likely to explore its trails. A 2011 survey commissioned by the National Park Service showed that only 7 percent of visitors to the parks system were black. (Blacks make up nearly twice that percentage of the US population.) Latinos were similarly underrepresented.

But if African-Americans don't figure in our notion of America's great outdoors, geographer Carolyn Finney argues, it is also because of how the story has been told, and who has been left out—black pioneers and ordinary folk whose contributions to the land have long gone ignored. Reclaiming those stories, she contends, could have huge implications for protecting our wilderness in the future.

Finney, an assistant professor of environmental science, policy, and management at the University of California at Berkeley, spent years researching African-Americans' connection to natural spaces. In a new book, "Black Faces, White Spaces: Reimagining the Relationship of African Americans to the Great Outdoors," she finds that that connection is rich, but also distinct and fraught—rooted in a history of racial violence and exclusion that sharply limited black engagement with nature. Those barriers, Finney writes, would come to shape our most basic perceptions about who cherishes nature and who belongs in it.

CORBIS

Charles Young of the 10th Cavalry in 1916.

Weaving scholarly analysis with interviews of leading black environmentalists and ordinary Americans, Finney traces the environmental legacy of slavery and Jim Crow segregation, which mapped the wilderness as a terrain of extreme terror and struggle for generations of blacks—as well as a place of refuge.

The book comes as the Park Service and other conservation agencies struggle to respond to America's changing demographics and diversify the ranks of visitors and employees. In doing so, they are increasingly turning to a national movement of black outdoor enthusiasts spearheading initiatives that celebrate African-American connections in nature. But to Finney, who serves as chair of the Relevancy Committee for the National Parks Advisory Board, any serious effort to broaden participation in the parks has to begin with getting the history right.

"There's this prevailing myth of black Americans as alienated from nature, as urban, as deeply unattached. Well, I push back on that, because I think we are actually very attached," said Finney, speaking about her work in 2012. "There are people of color who have invested blood, sweat, and tears into the land whose stories aren't acknowledged at all, let alone being recognized as people who care about the environment."

Finney spoke to Ideas from her home in Berkeley, Calif.

IDEAS: Describe your relationship to nature as an African-American girl growing up in New York.

FINNEY:My parents grew up poor in the South. When my father came back from the Korean War, they decided to move north to New York. His sister was living there and came up with two opportunities: He could be a janitor in Syracuse, or he could be a caretaker living on a wealthy estate just outside the city. That's where he and my mother moved. The estate was 12 acres, with a pond and lots of fish, vegetable gardens, snapping turtles, deer, geese....I can remember finding the strangest worm, knowing it was out of place and wondering how it got there. I had a favorite rock, which was carved out in the middle, and I would ride it like a horse. And of course I watched my parents tend to the land. The first conservationists I ever knew were my parents.

IDEAS: How did those experiences begin to shape your views about the relationship between black Americans and the outdoors?

FINNEY: After my parents left and moved to Virginia, neighbors of the estate would send letters whenever something significant happened. In 2005 or 2006, my father got a letter saying that there had been a conservation easement placed on the property. In perpetuity, nothing could be changed and no new buildings could be added. And they were thanking the new owner for his conservation-mindedness. In reading it, I couldn't help thinking, where was the thanks to my parents, who cared for that land for 50 years? That got me thinking about all the people in our history whose stories are unsung or invisible. We don't hear about them because nobody calls that "conservation." They don't fit into the way we talk about environmentalism in the mainstream. So how do we recognize and honor those other stories?

IDEAS: In your book you talk about the stereotype that blacks don't "do" nature. When did you start to bump up against that?

FINNEY: I think the first thing I came up against was just that black people are different, period—that being black didn't fit into the dominant culture's picture of a lot of things I wanted to do. "Black people don't do" fill-in-the-blank. So it makes sense that that would roll right into ideas about black people and the environment. In the late '80s and early '90s, I spent about five years backpacking around the world. And often times it was the Americans who would ask where I was from. Even though the way I am is very American, and I was dressed in backpacker gear and all that, it really messed with their minds that I could possibly be from the US. My presence, in nature, literally colored the way people were able to see me.

IDEAS: Who were some of the African-Americans environmentalists whose contributions surprised you most?

FINNEY: I interviewed so many people with amazing stories I had never heard of, stories I couldn't believe the mainstream environmental movement hadn't picked up on. Like John Francis, who spent 22 years walking across the US and Latin America to raise awareness about the environment. He did 17 years of that without talking! Or MaVynee Betsch, a black woman who gave away all her wealth, over $750,000, to environmental causes. Or Betty Reid Soskin, who at 92 is the oldest park ranger in the country, and who helped to get the Rosie the Riveter National Park on the books. What all of this says to me is the mainstream still has so much work to do to embrace and engage these stories, not just as black stories but as human stories that we can all relate to at a really basic level.

IDEAS: Your book draws parallels between pivotal moments in environmental history and pivotal moments in black history. How are they related?

FINNEY: Well, for example, the Homestead Act of 1862 made it possible for European immigrants to come here and go out West and grab large tracts of land, literally just by grabbing it before anybody else did. And you could just live on it for five years, and build a home and grow food, and it could be yours. That's amazing. And they were the only ones allowed to participate. That land, we know already, used to belong to Native Americans. And black people weren't allowed to participate at all.

On the heels of that, you have John Muir talking about preservation of the land and the idea of the national parks as these beautiful spaces that are going to be public treasures for everyone, every American....But meanwhile, enslaved people had just gotten freed, were given land, had that land taken away, and then were living under the threat of Jim Crow segregation for all those years afterward.

That's a real cognitive dissonance: There were words on paper saying these protected spaces were meant for everyone, but we know they weren't really meant for everyone, because everything else that was going on in the country at the time indicated that.

IDEAS:Your book describes recent efforts by the National Parks Service to broaden participation of African-Americans and other underrepresented groups in recreation and preservation. Why does broadening participation matter?

FINNEY: If you're someone who believes in the protection and preservation of a natural space, who's going to do that? It's going to be people. The changing demographics in this country mean that those people aren't going to look like the people from 60 or 70 years ago who were doing it. If you're going to engage people in terms of stewardship and protecting natural spaces, boy, there has to be a big overhaul. You can't talk about conservation without talking about people and difference and access. And making that connection is part of the big challenge.

NPR Story - Seafood

'The Great Fish Swap': How America Is Downgrading Its Seafood Supply

July 01, 2014 1:35 PM ET

Listen to the Story

36 min 24 sec

i i

i i hide captionPaul Greenberg says the decline of local fish markets, and the resulting sequestration of seafood to a corner of our supermarkets, has contributed to "the facelessness and comodification of seafood."

Paul Greenberg says the decline of local fish markets, and the resulting sequestration of seafood to a corner of our supermarkets, has contributed to "the facelessness and comodification of seafood."

What's the most popular seafood in the U.S.? Shrimp. The average American eats more shrimp per capita than tuna and salmon combined. Most of that shrimp comes from Asia, and most of the salmon we eat is also imported. In fact, 91 percent of the seafood Americans eat comes from abroad, but one-third of the seafood Americans catch gets sold to other countries.

Shrimp and salmon are two case studies in the unraveling of America's seafood economy, according to Paul Greenberg, author of the new book American Catch: The Fight for Our Local Seafood. Greenberg tells Fresh Air's Terry Gross about what's driving the changes in America's seafood economy and why you should buy wild salmon frozen when its out of season.

American Catch

The Fight for Our Local Seafood

Hardcover, 306 pages | purchase

On what Greenberg calls "The Great Fish Swap"

What I think we're doing is we're low-grading our seafood supply. In effect what we're doing is we're sending the really great, wild stuff that we harvest here on our shores abroad, and in exchange, we're importing farm stuff that, frankly, is of an increasingly dubious nature.

We export millions of tons of wild, mostly Alaska salmon abroad and import mostly farmed salmon from abroad. So salmon for salmon, we're trading wild for farmed. Another great example of this fish swap is the swapping of Alaska pollack for tilapia and pangasius [catfish]. Alaska pollack is the thing in [McDonald's] Filet-O-Fish sandwich; it's the thing in that fake crab that you find in your California roll. We use a lot of pollack ourselves, but we send 600 million pounds of it abroad every year. And in the other direction, we get a similarly white flaky fish — tilapia or pangasius — coming to us mostly from China and Vietnam. They fill a similar fish niche, but they're very different.

On why the U.S. exports the best-quality fish

We only eat about 15 pounds of seafood per year per capita. That's half of the global average, so there's that. The other thing is that other countries really are hip to seafood. The Chinese love seafood; the Japanese, the Koreans — they love seafood. They're willing to pay top dollar for it. We just aren't willing to do so. We want our food cheap and easy.

All of this fast-food commodification of seafood protein — because that's kind of what it is at this point — adds to that general preference for cheap stuff. Kind of in tandem and in league with that is the American tendency to avoid taste. ... Foodies [talk] about flavor and texture and the food movement and that kind of thing, and that's true of about 5 percent of Americans, but 95 percent of Americans really are not so into flavor. ... If we don't like the flavorsome fish — like bluefish, mackerel, things like oysters, things that really taste of the sea — if we don't like that, then we're going to go for these generic, homogenized, industrialized products.

On sending American salmon to China and back for cheap labor

A certain amount of Alaska salmon gets caught by Americans in Alaska, sent to China, defrosted, filleted, boned, refrozen and sent back to us. How's that for food miles? We don't want to pay the labor involved in boning fish and more and more of that fish that used to go make that round trip is actually staying in China because the Chinese are realizing how good it is, much to our detriment. ...

The labor is so much cheaper that it makes the shipping cost-effective. When you ship things via freighter, frozen, the cost per mile is relatively low compared to, say, air freighting or train travel or truck freighting.

On why you should buy wild salmon frozen, not fresh, if it's out of season

It's going to be frozen anyway. I sometimes will go to a supermarket in January and I'll see fresh, wild Alaska salmon sitting out there on ice and I just shake my head at it because I know that if it's January, there's a very little chance that that fish is fresh.

Nearly all of the salmon, when it comes into the processing plants in Alaska, gets immediately frozen. And that's great because if you freeze a fish right out of the water it will be of the highest quality that you can get out of a frozen product. So when you go to the supermarket in January, don't go to the fresh seafood counter for your salmon; go to the frozen bins and get those nice vacuum-packed Alaska salmon things. They're just going to be of higher quality.

On slave labor and the Thai shrimp industry

The largest shrimp producer for us right now is Thailand. ... It turns out, a certain amount of the shrimp that come to us from Thailand seems to be coming to us in part as the result of slave labor.

Shrimp are fed wild fish ground up and turned into meal — trash fish, they're called, just random fish that are trolled up in the South China Sea. It turns out, a large amount of that fish is being caught by boats in which the labor onboard are slaves and that fish gets ground up and sold to Thai shrimp farms.

On the decline of local fish markets

We don't want fish markets in our view shed. We don't want to smell them. We don't want to look at them. So they really have been banished from the center of our cities and sequestered to a corner of our supermarkets.

This is a process that aids all of the facelessness and commodification of seafood. ... Seafood has been taken out of the hands of the experts and put into the hands of the traders, so people really cannot identify the specificity of fish anymore. Because supermarkets rely on mass distribution systems, often frozen product, it means that the relationship between coastal producers of seafood is broken and so it's much easier for them to deal with the Syscos of the world, or these large purveyors that use these massive shrimp operations in Thailand or China, than it is for them to deal with the kind of knotty nature of local fishermen.

Tuesday, July 1, 2014

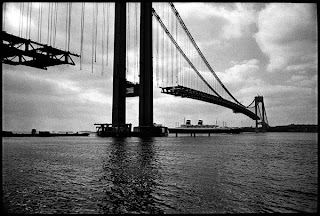

NY Times Article - Verrazon Bridge

Gay Talese Reminisces About Verrazano Construction

By JOSEPH BERGERJULY 1, 2014

Inside

Photo

In his coverage of the Verrazano Bridge, Gay Talese wrote about the daredevils who riveted and bolted the steel segments that made up the bridge; its designer, Othmar H. Ammann; and the homeowners displaced by the bridge's path. Credit Image by Damon Winter/The New York Times

Related Coverage

That bridge, the Verrazano-Narrows — the last major bridge built in the New York area before work began last year on a replacement for the Tappan Zee — is 50 years old this year. Already the United States Postal Service has issued a $5.60 priority mail stamp commemorating the opening of the bridge, at the time the world's longest suspension bridge. The Metropolitan Transportation Authority, the bridge's owner, is planning celebratory events but has not worked out details.

The writer Gay Talese chronicled the building of the Verrazano Bridge for The New York Times. Over five years, he produced a dozen articles on the rough-hewn high-altitude daredevils who riveted and bolted the steel segments that made up the two-mile bridge; its austere, brilliant designer, Othmar H. Ammann; and the hundreds of homeowners displaced by the bridge's path. He eventually wrote a book, "The Bridge," which has been republished by Bloomsbury Press, with a new afterword to catch readers up on the lives of those he profiled.

Photo

Sections of roadway were taken out by barge and lifted onto the bridge in sections. Credit Image by Barton Silverman

It is, after all, a very important bridge. It is responsible for turning Staten Island from a lightly populated, largely rural borough connected to the rest of the city by ferry into a place whose population is approaching 475,000, bigger than Atlanta or Kansas City, Mo. It is also a gateway to the city, among the first landmarks travelers by ship see as they enter New York's waters, and the starting line of the New York City Marathon.

Mr. Talese recently compared notes with a reporter chronicling the new Tappan Zee in the writing studio (the cellar) of his East Side townhouse. Mr. Talese, imperially slim at 82, was elegantly outfitted in a Brioni double-breasted blazer with the flourish of a crimson pocket square and shoes handmade by Vincent & Edgar on Lexington Avenue. He has had a fascination with the design and construction of things since his childhood in Ocean City, N.J., where his father, Joseph, an immigrant tailor from Calabria, sewed and shaped finely cut suits by hand.

"Tailoring is construction," he said. "You're dealing with stitches rather than cables. You're dealing with precision. Mr. Amman measured the bridge so that the Brooklyn tower and Staten Island tower are somewhat different in their placement because the curvature of the Earth affected how they would be placed. They had to be measured precisely like a suit. Things that last are well engineered."

Wearing the old hard hat he still keeps, Mr. Talese recalled walking the two-mile-long catwalk of the Verrazano, holding on by a steel rope "banister." A team of workers took him more than once to the top of one of the towers, where "large ocean liners looked like toy boats." He was not there when an ironworker, Gerard McKee, fell off the bridge, but he interviewed Edward Iannielli, who was much lighter than Mr. McKee and had tried to pull him up as he dangled from a catwalk's edge.

He hung around with ironworkers in the bars in Brooklyn, including one, the Wigwam, where the coterie of Mohawk Indians socialized, one of whom wanted to demonstrate his hospitality by offering to let him sleep with his sister.

Photo

Steel cables laid to form one of four suspension cables. Credit Image by Barton Silverman

"Some of the perks of being reporter are surprisingly presented to you when you least expect them," he said with a smile.

The suspension bridge whose construction he depicted cost $320 million to build in 1964 dollars. The three-mile replacement for the Tappan Zee — a cantilever-style architecture — is expected to cost $3.9 billion. Call it a paradox, but its toll is expected to be much lower than the Verrazano when it is completed in 2018. Though the amount has not yet been determined, crossing the current Tappan Zee costs $5, compared with $15 for the Verrazano.

As a reporter, Mr. Talese, who has written profiles of Frank Sinatra and Joe DiMaggio as well as books on such subjects as The Times and America's sexual evolution, has his eccentricities. Practically from the time he started working for The Times in 1953 as a copy boy and wrote his first story on the man who operated the Times Square headline "zipper," he spurned the standard reporter's spiral notebook for slim sections of cut-up white cardboard used by laundries to stiffen the packing of shirts. These days, working in jacket and tie even at home, he writes his articles in longhand, then types them up on his a 1980s-era IBM Wheelwriter 3 typewriter.

As a reporter, he said, "my instinct was to stay away from the big story."

"Do the small story," he said, "and it's not small if you do it well."

A Selection of Articles by Gay Talese

Mr. Talese chronicled the building of the Verrazano-Narrows Bridge for The New York Times.

- Nov. 22, 1964

Verrazano Bridge Opened to Traffic - Nov. 21, 1964

Staten Island Link to Sister Boroughs Is Opening Today - Nov. 15, 1964

Beauty Suspended - Aug. 25, 1964

Tough Bridge Builder Nears End of a Tough Job - June 19, 1964

Anger Lingering as Bridge Goes Up - Jan. 23, 1964

Bridge Delights 'Seaside Supers' - Jan. 1, 1959

Bay Ridge Seethes Over Bridge Plan

In seeing the bridge rise from when it was "a vision on the scratch paper of Mr. Ammann," he was particularly enamored of the ironworkers he met, especially the subspecies known as boomers. These were men, he wrote in the book, who streamed in from around the country in big cars to work on skyscraper, dam or bridge projects in the newest "boomtown," drink to excess and "chase women they will soon forget."

"These guys who put the rivets, they die but their work remains in place," he said. "There's no monument to these people."

Mr. Talese's last article about the bridge was of the opening ceremony. He described, with wry amusement, the procession of official limousines "that moved as slowly as a funeral procession" toward and across the bridge, with Robert Moses, the master public builder whose agency built the Verrazano, in the first car "wearing his battered gray fedora," Gov. Nelson A. Rockefeller and Mayor Robert F. Wagner in following cars, and Mr. Ammann, the great bridge designer of his age, in the 18th car. (Mr. Talese counted the cars. This is, after all, a reporter who found out that the two 695-foot towers were one and five-eighths inches farther apart at their summit than at their bases because of the Earth's curvature.)

In updating his book, Mr. Talese interviewed Joe Spratt, a 29-year-old construction worker who helped put up the antenna that topped off 1 World Trade Center at 104 stories.

"He talked about his father and grandfather and told me that when he was on the top, 'I look around and as I look south I see the towers of the Verrazano and I remember my grandfather Gene Spratt built the bridge.

" 'And if I turn north I see the Penn Central Building across from Madison Square Garden. That's my dad's building.' "

Mr. Talese added: "That's true of all these guys. They look around and everyone sees the skyline of New York as a family tree."

Thursday, June 12, 2014

NY Times Article

Noncompete Clauses Increasingly Pop Up in Array of Jobs

By STEVEN GREENHOUSEJUNE 8, 2014

Inside

Photo

A noncompete clause he signed prevented the stylist Daniel McKinnon from working near his previous employer for a year. Credit Katherine Taylor for The New York Times

BOSTON — Colette Buser couldn't understand why a summer camp withdrew its offer for her to work there this year.

After all, the 19-year-old college student had worked as a counselor the three previous summers at a nearby Linx-branded camp in Wellesley, Mass. But the company balked at hiring her because it feared that Linx would sue to enforce a noncompete clause tucked into Ms. Buser's 2013 summer employment contract. Her father, Cimarron Buser, testified before Massachusetts state lawmakers last month that his daughter had no idea that she had agreed to such restrictions, which in this case forbade her for one year from working at a competing camp within 10 miles of any of Linx's more than 30 locations in Wellesley and neighboring Natick. "This was the type of example you could hardly believe," Mr. Buser (pronounced BOO-ser) said in an interview.

Noncompete clauses are now appearing in far-ranging fields beyond the worlds of technology, sales and corporations with tightly held secrets, where the curbs have traditionally been used. From event planners to chefs to investment fund managers to yoga instructors, employees are increasingly required to sign agreements that prohibit them from working for a company's rivals.

Photo

John Hazen, head of his own paper company, says the noncompete clauses protect businesses. Credit Matthew Cavanaugh for The New York Times

There are plenty of other examples of these restrictions popping up in new job categories: One Massachusetts man whose job largely involved spraying pesticides on lawns had to sign a two-year noncompete agreement. A textbook editor was required to sign a six-month pact.

A Boston University graduate was asked to sign a one-year noncompete pledge for an entry-level social media job at a marketing firm, while a college junior who took a summer internship at an electronics firm agreed to a yearlong ban.

"There has been a definite, significant rise in the use of noncompetes, and not only for high tech, not only for high-skilled knowledge positions," said Orly Lobel, a professor at the University of San Diego School of Law, who wrote a recent book on noncompetes. "Talent Wants to be Free." "They've become pervasive and standard in many service industries," Ms. Lobel added.

Because of workers' complaints and concerns that noncompete clauses may be holding back the Massachusetts economy, Gov. Deval Patrick has proposed legislation that would ban noncompetes in all but a few circumstances, and a committee in the Massachusetts House has passed a bill incorporating the governor's proposals. To help assure that workers don't walk off with trade secrets, the proposed legislation would adopt tough new rules in that area.

Supporters of the pending legislation argue that the proliferation of noncompetes is a major reason Silicon Valley has left Route 128 and the Massachusetts high-tech industry in the dust. California bars noncompete clauses except in very limited circumstances.

"Noncompetes are a dampener on innovation and economic development," said Paul Maeder, co-founder and general partner of Highland Capital Partners, a venture capital firm with offices in both Boston and Silicon Valley. "They result in a lot of stillbirths of entrepreneurship — someone who wants to start a company, but can't because of a noncompete."

Backers of noncompetes counter that they help spur the state's economy and competitiveness by encouraging companies to invest heavily in their workers. Noncompetes are also needed, supporters say, to prevent workers from walking off with valuable code, customer lists, trade secrets or expensive training.

Joe Kahn, Linx's owner and founder, defended the noncompete that his company uses. "Our intellectual property is the training and fostering of our counselors, which makes for our unique environment," he said. "It's much like a tech firm with designers who developed chips: You don't want those people walking out the door. It's the same for us." He called the restriction — no competing camps within 10 miles — very reasonable.

"The ban to noncompetes is legislation in search of an issue," said Christopher P. Geehern, an executive vice president of Associated Industries of Massachusetts, a trade group leading the fight to defeat the proposed restrictions. "They're used in almost every sector of the economy to the seemingly mutual satisfaction of employers and individuals."

The legislative fight here pits two powerful groups against each other: venture capitalists opposing noncompetes and many manufacturers and tech companies eager to preserve them.

John Hazen, chief executive at Hazen Paper, said his 230-employee company in Holyoke, Mass., spends heavily to train workers on sophisticated machinery and elaborate papermaking processes.

"Noncompetes reduce the potential for poaching," said Mr. Hazen, whose company makes scratch lottery tickets and special packaging. "We consider them an important way to protect our business. As an entrepreneur who invests a lot of money in equipment, in intellectual property and in people, I'm worried about losing these people we've invested in."

The United States has a patchwork of rules on noncompetes. Only California and North Dakota ban them, while states like Texas and Florida place few limits on them. When these cases wind up in court, judges often cut back the time restraints if they're viewed as unreasonable, such as lasting five years or longer.

"In most states there has to be a legitimate business interest, and it has to be narrowly tailored and reasonable in scope and duration," said Samuel Estreicher, a professor at New York University School of Law.

Daniel McKinnon, who had been a hairstylist in Norwell, Mass., lost a court battle with his former employer who claimed that Mr. McKinnon had violated the terms of his agreement when he went to work at a nearby salon. Mr. McKinnon said that he did not think the original restriction — to wait at least 12 months before working at any salon in nearby towns — still applied because he had been fired after years of friction with the manager there. Shortly after being fired, he went to work at a nearby salon.

But a judge issued an injunction ordering him to stop working at his new employer.

"It was pretty lousy that you would take away someone's livelihood like that," said Mr. McKinnon, who for the following year lived off jobless benefits of $300 a week. "I almost lost my truck. I almost lost my apartment. Almost everything came sweeping out from under me."

He resisted the idea of traveling miles from his apartment to a new salon, saying that would have meant an unpleasant and costly commute.

Non-compete agreements have a usefulness - if I sell my business to you, you don't want me to open up the same business next door and lure...

Non-competes are mostly a ploy to raise employee switching costs -- they are a significant 'gotcha' for management in the many states where...

Wendi S. Lazar, an employment lawyer in Manhattan, said she saw an increase in litigation to enforce noncompetes. "Companies are spending money, hiring lawyers, to go after people — just to put the fear of death in them."

State Representative Lori Ehrlich, one of the main sponsors of the Massachusetts legislation to bar noncompetes and vice chairwoman of the Joint Committee on Labor and Workforce Development, said that many people had complained to her about the restrictions being set for employees.

"It's hurting growth in the economy by decreasing worker mobility and squelching start-ups," Ms. Ehrlich, a Democrat, said. "They're hurting families by making it so people are unable to work for an extended period of time. This has increasingly become exploitative to workers."

Matthew Marx, a professor of entrepreneurship at the M.I.T. Sloan School of Management, said a recent study he did found that half of the nation's engineers had signed noncompetes, with a third lasting more than a year, and some more than two years.

"Where noncompetes are not enforced, there's a more open labor market — companies compete for talent," he said. "We used to have a saying at the Silicon Valley start-up where I worked, 'You never stop hiring someone.' They can go where they want. People are free to leave and start companies if they're not happy."

Professor Marx said California's ban on noncompetes was a major reason Silicon Valley was thriving. If a few employees there have an innovative idea and their bosses don't want to pursue it, they can leave to found a start-up. But in Massachusetts, if employees with noncompetes bring that innovative idea to their boss and it is rejected, they are stuck — or they would have to leave the company and wait a year before they could pursue their new idea. (Or they could move to California, where the courts would not enforce the Massachusetts agreement.)

Mr. Geehern of Associated Industries of Massachusetts denied that the California economy, with a 7.8 percent jobless rate, was doing better than the Massachusetts economy, with a 6 percent rate.

"If noncompetes are so onerous and burdensome, why aren't we seeing a significant migration of talent away from the companies that use noncompetes toward the companies that don't use them?" he said. "The companies that use noncompetes still attract plenty of the best and brightest."

Michael Rodrigues, a Democratic state senator from Fall River, Mass., said the government should not be interfering in contractual matters like noncompetes. "It should be up to the individual employer and the individual potential employee among themselves," he said. "They're both adults."

NY Times Article

Watches, Watches All Around, but Not a Timex to Be Found

In Two Sales, Bonhams Is Auctioning Off Rare Timepieces

By JAMES BARRONJUNE 12, 2014

Jonathan Snellenburg, the director for watches and clocks at Bonhams, the auction house on Madison Avenue. Credit Ozier Muhammad/The New York Times

For this short history of time — not the cosmos-looking Stephen Hawking kind of time, but the kind kept by the ingenious and occasionally impractical watches that collectors fancy — Jonathan Snellenburg had the visual aids ready.

As visual aids go, they were shiny and expensive.

One was as bright as when it was the constant companion of a Pennsylvania Railroad employee and cost only a fraction of its current value, which Mr. Snellenburg estimated at $4,000 to $6,000.

Another visual aid was once a possession of a man whose other possessions included the Boston Red Sox when they won the World Series with Babe Ruth on the pitcher's mound. It was worth even more than the first one — $8,000 to $12,000, by Mr. Snellenburg's calculations.

Mr. Snellenburg will not have those visual aids after Thursday, assuming the morning and afternoon unfold as he expects them to.

Mr. Snellenburg is the director for watches and clocks at Bonhams, the auction house on Madison Avenue that has scheduled two sales of timepieces — in the morning, several dozen wristwatches and pocket watches, along with a Cartier clock from the estate of the movie actress Norma Shearer; in the afternoon, more than 300 pocket watches from a single collection.

Photo

Clockwise from top left, a double enamel plated portrait fob watch, circa 1890; a watch owned by Joseph Lannin, a former owner of the Boston Red Sox; a pocket watch from the early 19th century; and a crystal plate pocket watch made by the Waltham Company in the late 19th century. Credit Ozier Muhammad/The New York Times

The Bonhams sale follows watch sales at Sotheby's on Tuesday and Christie's on Wednesday that commanded even higher prices than those expected at Bonhams. At Sotheby's, a Patek Philippe wristwatch begun in 1903 and completed 20 years later sold for $2.965 million, well above the presale estimate of $800,000 to $1.2 million.

Some of the watches in the Bonhams sale are older — much older. One of the oldest is a plain-looking silver pocket watch signed by Thomas Harland, who, Mr. Snellenburg said, is often mentioned as one of the earliest watchmakers in the American colonies.

Like luxury watchmakers of a later era, Harland believed in advertising, judging by what Mr. Snellenburg quoted in the auction catalog. Harland placed an ad in a Connecticut newspaper in 1773 saying that he "makes, in the neatest manner, And on the most improved principles, horizontal, repeating and plain watches in gold, silver, metal or covered cases."

But different artisans made the parts — there would have been a dial maker, an escapement maker and many others. "The question that everyone asks when you see a watch signed by Thomas Harland is, how much of it did he actually make himself and how much was made out of imported parts?" Mr. Snellenburg said. "Most watches that you see signed in colonial times in America are simply English imports."

He said the watch in the sale "does not appear to be totally English, so if he did not make part of it, he certainly repaired part of it." It has a brass escape wheel, gold hands and a presale price estimate of $7,000 to $9,000.

The Civil War brought "the first watches people could afford," he said, and mass production established the Waltham Watch Company as a predecessor of the Detroit automobile giants that marketed a model for every price point — good, better, best.

Photo

A Patek Philippe platinum wristwatch with diamond numerals and a snake bracelet. Credit Ozier Muhammad/The New York Times

"There was the Chevy case, the Buick case and the Maserati case," he said, but the differences were mainly cosmetic.

The parts inside the case — the wheels, springs and levers — were essentially the same from watch to watch. "But depending on the price point the watch might be sold at," he said, "they would finish that basic movement in a number of quality grades." He said that Waltham made more than 35 million watches between 1850, when it was founded, and 1957, when the original company went out of business.

And then there was the watch that belonged to Joseph J. Lannin, the owner of the Red Sox. The movement has 23 jewels — diamonds, of course, not the usual rubies — that are set in gold, Mr. Snellenburg said.

"This is the Maserati," Mr. Snellenburg said. "A watch to be given for special occasions."

Indeed, according to the inscription on the watch itself, it was given to Lannin at Fenway Park on Aug. 3, 1915, a few months before the team won the World Series.

It has a four-leaf clover on the 18-karat gold case, and each leaf has a diamond. But it was thinner than many earlier pocket watches, and that pointed to the future — perhaps not as far ahead as free agents, steroids and more World Series championships for the Red Sox, but certainly beyond Lannin's lifetime. (He died in 1928 at age 62.)

"That slim, smaller pocket watch evolved into the wristwatch," Mr. Snellenburg said, "but in the early part of the 20th century, certainly until the 1940s, wristwatches were not considered terribly masculine. Real men carried pocket watches."

Wednesday, June 4, 2014

My Favorite Animal

=

Monday, May 12, 2014

Tuesday, April 29, 2014

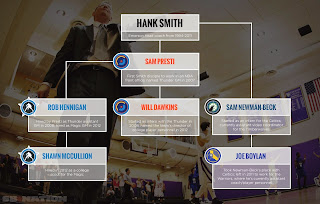

The NBA's Improbable Pipeline

How alumni from tiny Emerson college infiltrated pro basketball's front offices

"East Boston High," he says, starting a list. One after another, he keeps adding to it, rattling off the names of nearby schools with gymnasiums: "Simmons College, Mount Ida, Mass College of Arts, Tobin Community Center, Don Bosco High School." He finally pauses. "Umm," he racks his brain for more, then starts listing again, "Chinatown YMCA, Emmanuel College, Suffolk University." His voice is coarse, like someone who yells too much. "I'm trying to think of all the ones," he says, struggling to remember the places the school's basketball team called home. He almost immediately snags another from his memory as he lets out a quick, nostalgic laugh that's almost a sigh and says, "Boston Latin High School. The first and only time I've ever been there is for a home game about 10 years ago."

That's when Shawn McCullion, a college scout for the Orlando Magic since 2012, was an assistant basketball coach at Emerson College, a small Division III school located in the heart of Boston. Until 2006, the school had no gym. The team hopscotched around Boston and its suburbs claiming gym after gym as their home, whether for one game or many.

"I had to MapQuest a home game once," McCullion says. He was getting ready to head to Emerson to pile into vans with his team and drive to the Chinatown YMCA. Then, 10 minutes before he was set to leave his house, he learned the Y staff had ripped out all the bleachers leaving no place for the fans to sit. They had to find somewhere else to play. Fortunately, East Boston High School was available. Unfortunately, McCullion had no idea how to get there.

"This is a place I have never been to in my entire life and that was a home game for a college basketball team," McCullion says incredulously. But MapQuest came through and Emerson made the game.

Not that many fans did. The YMCA sans bleachers probably would have been fine.

Emerson isn't exactly a sports powerhouse. The school, with a combined enrollment of less than 4,500 students, is in Boston's Theater district, just off the Boston Common. For a school that touts itself as "the nation's premiere institution in higher education devoted to communication and the arts in a liberal arts context," it's the perfect location. Notable alum include former "Tonight Show" host, Jay Leno (1973), "Happy Days" star Henry Winkler (1967), actor and comedian Denis Leary (1979), Maria Menounos (2000), the host of "Extra," and numerous journalists, authors and film and television producers.

The Boston school somehow became a breeding ground for NBA front office positions.

Shawn McCullion, now a scout for the Magic, coaches on the sidelines at Emerson. (Photo credit Pete Keeling)

Shawn McCullion, now a scout for the Magic, coaches on the sidelines at Emerson. (Photo credit Pete Keeling)

A great place, unless, of course, you're interested in being a sports star. "The most popular sport on campus now is Quidditch," says McCullion. He isn't kidding.

Still, a small group of Emerson alumni has been nearly as successful in professional basketball as those from far more recognizable schools, like Duke or Kentucky. No, the Emerson guys didn't become NBA stars like Grant Hill or John Wall, but they still made it to the NBA. Over the past 15 years the Boston school somehow became a breeding ground for NBA front office positions.

Before he became a coach, McCullion, a Nashua, N.H., native who played a total of seven minutes of high school ball, played for Emerson, transferring after playing junior varsity basketball at Plymouth State College in New Hampshire.

It was the fall of 1994 and McCullion only went to the athletic department because he wanted to try out for the golf team. In the middle of the room was a banquet table with sign-up sheets for each sport. "That was how they were recruiting at Emerson at the time," McCullion says.

The basketball sign-up sheet was right next to "Golf." The athletic director talked him into signing up; there was a new coach and he needed players, even those with only seven minutes of high school experience.

Midway through the first official practice, McCullion rethought his decision to play. The team hadn't stopped sprinting all practice, it seemed, and in the middle of their fifth or sixth "minute drill," racing the length of the court time and time again, McCullion bolted. He went straight to the shower stall at the Mass College of Art gymnasium, dropped to his hands and knees and started throwing up. Assistant coach Bruce Seals, who had played three seasons with the Seattle SuperSonics in the 1970s, followed McCullion into the showers. He stood over him, took off his glasses and said, "I feel ya, young fella. I feel ya, young fella."

The new coach, Hank Smith, was unlike any McCullion had ever experienced. Smith decided that what Emerson lacked in talent, they would make up with conditioning. McCullion wanted to quit — he thought about it the entire night after that hellish first practice — but he didn't want to leave the team shorthanded, so he kept on showing up.

The running and running and running worked. The kids with no home gym could play. In the previous five seasons, Emerson had won a total of only 21 games. In Smith's first season, they won 17. In McCullion's senior year, Emerson won the Great Northeast Athletic Conference championship.

Today, as a college scout for the Orlando Magic, McCullion is responsible in part for the club's selection of players like shooting guard Victor Oladipo, an emerging star. None of it would have happened if not for Smith. He says the day he didn't quit the team was, "Without question the most important day of my life."

One day last year he was sitting in Steve Wojciechowski's office discussing NBA prospects. Wojciechowski, recently named head coach at Marquette, was then the associate head coach at Duke, second in command to Mike Krzyzewski, one of the most successful coaches in the history of college basketball. The conversation turned to Hank Smith, whom Wojciechowski had once met. Wojciechowski said, "Coach Smith is a pretty good coach I heard."

"Let me put it in perspective," McCullion said. "There's only two people walking the face of the earth that have coached two general managers in the NBA. One of them is Hank Smith. The other one's the guy upstairs. (Krzyzewski.)"

That says something.

***

The NCAA says something, too, highlighted on its Facebook page: "There are over 450,000 NCAA student-athletes, and just about every one of them will go pro in something other than sports." It's true. The odds of making an NBA roster are mind-bogglingly slim. And the odds of becoming the general manager of an NBA team are even more preposterous.

Yet two Emerson alums have done just that: Sam Presti, Class of 2000, is the general manager of the Oklahoma City Thunder and Rob Hennigan, Class of '04 is the Orlando Magic's GM. In the entire history of the NBA, only two colleges other than Duke and Emerson — UCLA and Wheaton College — have claimed two NBA GMs at the same time.

But that's not all. Four more Emerson alums are working in basketball operations for NBA teams and may one day move up. In addition to McCullion, Will Dawkins is the director of college player personnel for the Thunder, Joe Boylan works for Golden State as assistant coach/player personnel (Note: Boylan is the author's cousin), and Sam Newman-Beck is an assistant video coordinator for the Minnesota Timberwolves. Somehow, Hank Smith took a small art school in Boston and created a feeder school for the NBA. It's as if alumni from the University of Kentucky basketball program under John Calipari started winning Oscars and Pulitzer Prizes.

Smith's coaching résumé may not compare to Krzyzewski or Calipari's, but his influence in professional basketball might be longer lasting than either man's. But just as it has become visible, the Emerson pipeline may be done.

Hank Smith doesn't coach anymore.

***

Smith, who is married with two grown children, graduated from Brighton High School in Boston in 1974. Despite the presence of the champion Celtics, the city was hardly a basketball hotbed — Boston was a hockey town. But not to Smith. He was all basketball until a knee injury derailed his playing career. He didn't go straight to college. Instead, he got a job as an operations manager at an office supply wholesaler. But that didn't keep him away from the game. A gym rat, he coached youth teams at the West End Boys Club and semi-pro teams all around New England. Dennis Richey, one of Smith's best friends growing up, refers to the teams as "AAU teams before there were AAU teams." Smith just had to be near a basketball court. "I wasn't getting paid or anything," he says, "I just coached to coach."

He took his first paid coaching job in 1988 as the freshman coach at Dedham High School in Dedham, Mass. Three years later, he moved to Framingham State College in Framingham, Mass. There he realized that if he wanted to coach at the collegiate level, he was going to need a degree, so he enrolled in classes, eventually earning a bachelor's degree at Franklin Pierce College.

Smith was tireless when it came to his team. Jim Todd, who has served on the coaching staff for five NBA teams, most recently the New York Knicks, once coached at Salem State College and remembers constantly seeing Smith on the recruiting trail at high school and AAU games. "Every time I went out to a game," Todd says, "he was there." So Todd hired him on at Salem State in 1993. He says Smith was knowledgeable of the game in an "X's and O's sense," but he was also "relatable," a perfect fit for a college coach who was going to have to work with young kids.

He prepared them the only way he knew: by running them ragged.

Hank Smith coaches his players. (Photo credit Pete Keeling)

Hank Smith coaches his players. (Photo credit Pete Keeling)

After a year under Todd, Smith took the head coaching job at Emerson. He turned the program around almost instantly, insisting his team played hard and pressing in every single game. He prepared them the only way he knew: by running them ragged.

It started with the minute drill: Sprint from one end of the court to the other. Then go back. Do it again, down and back. And again. One more time. Then one last time. Ten length of the court sprints (five down and five back) in 60 seconds, the cornerstone of Hank Smith's coaching method. If anyone didn't finish all five down-and-backs in 60 seconds the entire team would run them again. The same was true if they missed the end line. Add in defensive slides, backboard touches, pushups and bear crawls, and practice was one constant conditioning session.

"It doesn't sound that bad when you write it out," says Ben Chase, who played for Emerson from 2004 to 2008 and is now the assistant coach of Houston Baptist University's women's basketball team, "but it was brutal."

In Chase's first year, before any official practices, the players met for captain's practices and were introduced to the minute drill and every other exercise they would face in practice playing on an outdoor, asphalt court in the Back Bay Fens, near Fenway Park.

Still, playing pick-up games in frigid weather and running sprints while wearing mittens to fend off the cold barely left them prepared for what was to come. The players dubbed the first week of practice under Smith, "Hell Week," rising at 5:45 a.m., piling into vans for a 40-minute drive to the gym at Pine Manor College, then practicing until 9 a.m. The rest of the year wasn't much easier.

Alex Tse, a member of Smith's first Emerson team, started the year at 150 pounds. When he hopped on the scale at the end of the season, it read 135. Tse doesn't work for an NBA team, but he's yet another successful Emerson basketball alum: He's a screenwriter in Hollywood, co-writing the 2009 film, Watchmen. He named his production company Minute Drill Productions.

Smith's coaching style didn't make it any easier. A yeller, Smith barked instructions at his team almost non-stop, his nasally voice echoing across the gym alongside the squeaking sneakers and heavy exhales bellowing from exhausted players. And on the sideline during games, Smith was equally demonstrative. He almost always scowled. He wore glasses, but the clear lenses only seemed to magnify the intensity in his eyes. It was D-III basketball coached as if it was the NBA Finals.

Roger Crosley was the coordinator of athletic operations at Emerson from 2003 to 2011. He laughs and says that a lot of the stuff Smith used to yell probably couldn't be printed. "For someone that had as crazy a sideline demeanor as he did, he got amazingly few technicals," Crosley says. "That game had 100 percent of his focus. He never thought about anyone or anything else other than coaching that basketball game."

Yet Smith was no Bobby Knight, ruling by intimidation and fear, breaking players down to build them back up and not worrying about the castoffs who couldn't cut it, able to cherry-pick replacements from among 5-star recruits. At Emerson, he primarily worked with what he had, semi-skilled players who sometimes thought of themselves as actors and poets.

Smith yelled, but he also cared deeply about his athletes. And his players loved it. For many, who had grown up in the soft embrace of the suburbs, learning to push themselves beyond what they thought they were capable of was a transformative experience.

"Coach was pretty dynamic," says Newman-Beck, who graduated from Emerson in 2009 and is now an assistant video coordinator with the Timberwolves. "He looked a little crazy at times. But you could tell he really cared about you. He just had a unique ability to get the most out of us."

He got the most out of them by not only yelling instructions, but also by being a friend. A lot of coaches can be off-putting by yelling, but the Emerson players knew Smith wanted the best for them. Plus, they had fun.

"He's incredibly passionate and a tireless worker, and prepares ad nauseam for his upcoming game or practice," says Hennigan, the general manager of the Magic. "But at the same time he doesn't take himself too seriously and he has an ability to create an interpersonal bond with you because he likes to joke around, he likes to bust balls."

Rob Hennigan, who became general manager of the Magic at age 30 in 2012. (Photo credit Getty Images)

Rob Hennigan, who became general manager of the Magic at age 30 in 2012. (Photo credit Getty Images)

***

"I think the thing about Emerson teams and the family that we have," Smith says, "is that we never try to put anyone bigger than anybody else."

In his first home game as Emerson coach, he benched the starting point guard because he was five minutes late for a practice. Tse, who says he would have been cut from most college basketball teams, started in his place. No matter the talent level, Smith would find each player a role. Tse compares it to the way hyperactive guard Randy Brown found playing time on the Bulls championship teams in the '90s.

It is fitting that many Emerson teams practiced on outdoor courts in Boston, that's where Smith honed his skills and philosophy as well. His approach was shaped while growing up in Boston in the 1960s and '70s watching greats like Red Auerbach and Bill Russell's Celtics dominate the NBA.

Ringer Park off Commonwealth Ave., in Allston, a working-class neighborhood flanked by Boston University and Boston College, was where many young, crazed Celtics fans lived out their basketball fantasies in Smith's younger years. "He was good," says Richey, who grew up playing basketball with Smith, "a very cerebral basketball player." Richey was three years behind Smith at Brighton High, so they were never on the school's team at the same time, but they played at Ringer Park constantly. BC and BU players would sometimes even show up for pick-up games. It was a cutthroat atmosphere: To keep the court you had to win. "It was a battle," Richey says, sighing, "Everything was a battle." Smith never wanted to leave that court.

He was intense, competitive, unforgiving. His players reveled in it.

As his competitiveness mounted on the playground, so did his knowledge and understanding of the game. Richey played for him on a team sponsored by Bromfield Pens in the late-'70s and early-'80s.

In one of his first adult coaching jobs, Smith was already a spitting image of his future self. "Always very intense," Richey says of Smith on the sideline back then. "Very competitive, very intense. Always wanting to do things the right way. With Hank there's a right way and a wrong way, no gray area, no in between."

Many coaches learn from the coaches they grew up with, but Smith was mostly self-taught. Richey says he and Smith didn't have any good coaches growing up: "We watched a lot of basketball, we played a lot of basketball, we kind of learned on the fly, and he was at the forefront of our group with that."

He carried his belief of right and wrong to every coaching stop he had. Once he had his own program at Emerson, he could impart those lessons he learned through the game of basketball on his players. He was intense, competitive, unforgiving. His players reveled in it, especially those who went on to the NBA.

"I don't so much call it an 'It factor,'" Hank Smith says of the six Emerson alums working in NBA front offices, "I just know that with every one of them, number one, they're all very intelligent."

Second, says Smith, is that they were willing to accept responsibility; they were very mature. He credits their families for that.

Third, Smith says, "They were always willing to do more and more for their team."

Smith may credit his players, but his players credit Smith, arguing that he prepared them for any type of job and is the biggest reason they've been successful in the NBA. At Emerson, they learned that no amount of work was too much, that talent wasn't everything, that effort and teamwork and playing smart mattered more.

Under Smith, basketball was demystified. They learned a workmanlike approach to the game, and now, in the NBA, they treat it like any other job. They aren't in awe. They are smart, creative guys — they went to an art school, after all — but smart creative guys who also have drive. Presti, for instance, is part of a new generation of NBA GM's who have embraced analytics — he's spoken at MIT's Sloan Sports Analytics Conference, appearing with Bill James on a panel discussing personnel decisions. ESPN's Bill Simmons even called him "a cool-ass nerd who reads blogs."

Whatever works.

Sam Presti, who has served as the Thunder general manager since 2007. (Photo credit Getty Images)

Sam Presti, who has served as the Thunder general manager since 2007. (Photo credit Getty Images)

***

The job of an NBA general manager is to put together a team, not just to assemble talent, but also to find a group of players and coaches that gel. A general manager needs to be able to see the team as a whole, dispassionately, yet also a group that can work together passionately. The same goes for a coach or a video intern. To work in the front office of an NBA team, all pieces of the puzzle need to be assembled and put together.

"Look at yourself honestly and understand really where you fit within the team concept," Presti says when looking at the lessons Smith imparted on him. "Really give yourself up for the collective good." He isn't giving away the tricks of the trade to how he puts together the Thunder roster — there is much more to it than that — but it's not a bad starting point. "Understanding that the collective group is the most important thing," he adds, "really forcing yourself to be a critical self-evaluator and an honest self-evaluator. I think those are really important qualities regardless of what line of work you got in to."

Players who donned the Emerson jersey under Smith learned to accept their role on the team. Smith says, "How do you maximize everybody and then cover the weaknesses everyone has?" That was his approach, and his players have taken that forward.

Presti was the first. With his stylish glasses and close-cropped, reddish hair, the lean Presti looks more like a CEO of a startup than an NBA executive. He is calculating when he speaks, careful to say the right thing, and tries to maximize his team in any way he can. He has tweaked the Thunder countless times in his effort to build a champion. They made the NBA Finals in 2012 and even after trading James Harden for contractual reasons, the Thunder have adjusted. With Kevin Durant and Russell Westbrook, the Thunder remain a serious threat to make the 2014 Finals as well.

"There was a seriousness to Sam that was different from any college kid," Tse says of Presti. He remembers that Presti hit the game-winning free throws in one of his first games with Emerson. Tse recalls being pumped and saying something to get Presti jacked up, but, as Tse says, "Sam was just matter of fact about it and described why he was prepared for that moment." Tse laughs, and keeps going, "And I was like, 'OK, this dude's serious.'"

After he graduated from Emerson in 2000, he attended a camp in Colorado where he met San Antonio Spurs basketball chief R.C. Buford. As Buford refereed a scrimmage, Presti, hyper focused, begged for an internship. It worked. He got the internship. Subsequently, he worked his way up the ladder with the Spurs to become assistant general manager — it helped that Presti, at age 24, persuaded Spurs coach Gregg Popovich to take a closer look at Tony Parker in the 2001 draft after seeing footage of Parker playing in France. He was with the Spurs for their NBA titles in 2003, '05, and '07. Then he left for Seattle to take over as general manager. He was 30 years old.

The SuperSonics left Seattle for Oklahoma City in 2008 and became the Thunder. That same year, Presti hired another Emerson alum, Rob Hennigan as his assistant general manager. "I owe everything to Sam," Hennigan says. "He's the one that gave me that chance and he's the one I was able to learn from all these years."

With Hennigan and Presti in the league, the pipeline from Emerson to the NBA was in place.

Sam Presti (Photo credit Getty Images)

Sam Presti (Photo credit Getty Images)

Hennigan followed a path similar to Presti's. After Emerson, where he was the all-time leading scorer, he took lessons from Coach Smith and applied them to his career. He began as an intern with the Spurs in 2004, choosing that position over a low-paying TV reporter's position in Alaska — before joining the Thunder. Then, in 2012, Hennigan moved on, at age 30, taking the general manager position with Orlando, where he has entirely turned over the roster, freeing them from onerous financial constraints and setting them up for the future. Emerson College not only produced two general managers, but two of the youngest GMs in the history of the league.

With Hennigan and Presti in the league, the pipeline from Emerson to the NBA was in place. More and more of Smith's players looked toward basketball as a career. Dawkins, Newman-Beck and Boylan were all on Emerson's 2007-08 team that had only one player taller than 6'4 yet still finished 15-3 in the GNAC. Over the next three years, building on the reputations of Presti and Hennigan, each scored a job in NBA.

Dawkins accepted a front office internship with Oklahoma City in 2008. Newman-Beck got his start with a video internship with the Boston Celtics before joining Minnesota as assistant video coordinator, where he still works, watching footage of Ricky Rubio doing unthinkable things with the basketball.

Boylan took a more circuitous route. The only Emerson player in the NBA not from New England, Boylan transferred to Colorado College after his freshman season. He immediately knew he made a mistake. He went back to Emerson — and Smith — just a semester later. "Before he left he was a really smart, confident guy who talked a big game, but there was something missing," Chase says. "When he came back, he was totally focused. When he came back he was a leader." After graduation, he worked with Tim Grover, a personal trainer famed for working with Michael Jordan, and in 2009, he got into coaching, working with the Portland Red Claws in Maine. When Newman-Beck left the Celtics for the Timberwolves, Boylan took his place, and then moved cross-country in 2011 to work for Golden State as video coordinator. He's still there, only now he's assistant coach/director of player personnel. Boylan, who resembles Celtics head coach Brad Stephens, sits one row behind the bench. During Warrior games, his head pops up after each play to get a better look at the court like he's part of a Whac-A-Mole arcade game.

Many coaches have a "coaching tree," people who have played or coached under them and are now at different schools. Krzyzewski's includes Tommy Amaker at Harvard, Mike Brey at Notre Dame and Johnny Dawkins at Stanford. Tom Izzo's includes Tom Crean at Indiana and Stan Heath at South Florida.

Former Knicks assistant Jim Todd sees something similar with Smith and his progeny. He likes to tease Smith, saying, "It's not the coaching tree for you, it's the manager tree."

Before 1995, Emerson basketball was an afterthought. By 2010, with five alums already in the league, there was something about this small art school in Boston.

And everyone says it's because of Coach Hank Smith.

***

There is, however, one person who does not credit Smith. And that is Hank Smith himself.

In an age where college coaches are often bigger than the teams themselves (thank the one-and-done system making the coach a much more stable face of a university), Hank Smith is nearly invisible, appearing for an interview about Presti or Hennigan every once in a while, but almost never speaking about himself. He is the embodiment of the athletes he coached. He stays out of the limelight. During all his years at Emerson, neither the Boston Globe nor the Boston Herald even saw fit to profile one of the most successful coaches in the city. He just keeps his head down and works his butt off. He is the anti-Calipari.

His former players are much the same. Presti credits Smith with his rise in the NBA. Hennigan says it's because of Presti and Smith. They all pass the buck along to someone else. And for everyone but Smith, it's Smith. "I don't want to make it out like I made them like this," he says.

But when asked about Smith, his players, from Presti the GM to Tse the screenwriter, all say versions of the same thing. It's not so much the X's and O's they learned from Smith, but the answer to a question.

"What makes you a man?" Smith always used to ask.

"My description of a man is someone who accepts responsibility," he says. "As long as you're here you are going to accept responsibility for everything you do that involves our team in any form." Smith became a man on the Ringer Park courts. He became a man while working a full-time job and still finding time to coach the boys' club and every semi-professional team he could find.

To the players he coached, learning to be a man means the same thing to all of them: take responsibility, don't make excuses.

The story of how current Suns general manager Ryan McDonough became assistant GM of the Celtics at just 33 years-old, helping to usher in a new age of player evaluation.

The players did exactly that at Emerson, where they didn't have a home court until 2006 and where they had to wash their own gold and purple uniforms, sometimes practice in a playground and play knockout for a pair of socks. They claim that's why they were successful. Not only in places like Hollywood, where Emerson grads are supposed to pop up, but the NBA, where they aren't.

Finishing four years under Hank Smith was like passing through a crucible. The alums have an understanding. Tse says, "If you can play four years and you can finish your time with him, you've passed one rung of the background check."

"The ones that bought into Smith," says Crosley, "boy, I have never seen a group of more committed individuals than Emerson's basketball players."

He remembers that after the last game of each season, Smith would keep his players in the locker room. The seniors were given a chance to talk. He wanted them to impart what Emerson basketball meant to them, what it should mean to the underclassmen. The final team meeting of the season, and for some players, their careers, would last three to four hours.

"Every cliché about a sports team," Alex Tse says, "'here are the lessons in life you're gonna learn.' Ninety percent of the sports teams, you're not gonna get that shit. They preach it, but it doesn't happen. Here, it was real."

"[Coach Smith] was always emphasizing the reflection of basketball and real life," Boylan says. "So much of it was what they say college athletics is all about, developing skills and determination. Being able to take, take, take, take and just keep on fighting with a smile on your face and then ultimately getting rewarded."

Not that it always worked that way.

In January 2011, Smith was abruptly fired as Emerson's head coach. Although the athletic department announced that he decided to leave, William P. Gilligan, the vice president of information technology who oversaw athletics told the Berkeley Beacon, Emerson's school paper, "the decision was made by the College to no longer, in essence, to no longer have Mr. Smith as the coach."

Just like that, Hank Smith was gone as coach at Emerson.

No one will really talk about what happened. Certainly not Smith. But at art-oriented Emerson, a coach like Smith was, increasingly, an anachronism, old school, perhaps not quite the image the school wanted to continue to put forward.

The team's alumni network didn't take it kindly, and the relationship between the Emerson basketball family and the school is still tense. McCullion says, "I don't really feel like I have an alma mater."

"Hank was a good coach," says Crosley. "He had players that loved him, he loved his players ... He was a winning coach. He didn't cheat. His sideline antics could be a little entertaining at times, but he wasn't Bobby Knight throwing chairs across the floor. He was a good coach and a good man and he deserved a better fate at Emerson."

All Smith will say is this: "I was really luckier than they were."

"All those people, all the good things they brought to me was incredible."

***

Emerson has a gym now. It's three stories underground at 150 Boylston, next door to an M. Steiner & Sons piano store, just off Boston Common.

There's a small plaque next to the elevators in the lobby. In 2006, at one of Emerson's first home games in their gym — the gym that many Emerson alums never had — the Emerson basketball family gathered in that lobby after the contest, standing before a flimsy, black drape hanging on the wall.

McCullion addressed the small crowd. He told a story about Coach Smith calling him in 2000 to tell him Presti was going to be an intern with the Spurs. He said that Coach guaranteed Presti would be a general manager some day. "The first day Sam got the internship, Coach knew that he was going to be a general manager," McCullion said. "And after that, whenever he said anything, I really listened." Everyone laughed. McCullion told everyone that Hennigan was next. Then he pointed to Dawkins and Boylan. Coach Smith had given them a stamp of approval, and even then, McCullion knew they were going to be big.

Then he peeled away the drape and revealed a plaque that reads:

In honor of

Coach Hank Smith and family

-gift of your players

to whom you have dedicated so much

2006

The plaque is still there, one of the few reminders of Hank Smith's time at Emerson, but the alums just don't feel like it's home. They were fine without a home gym before, they'll be fine again. They've accepted responsibility, there's nothing they can do about it now.

Besides, there's another sign of Smith's accomplishment, and that of the young men he coached. It's not just in the front offices of the NBA, or on the court, where players who Hank Smith would have loved to coach have been picked out by some of the men he did to play a role, and find a place, on a team in the NBA.

It's also in the stands, where one more Emerson alum is employed in the NBA now. Smith is Emerson's de facto seventh NBA staffer. He works for Presti and the Thunder as a special assignment scout.

And if you know where to look, you can sometimes find him sitting in the stands of a gym somewhere, maybe in the NBA, maybe in some small, out of the way college, some place where you might not expect to find an NBA scout. He's the guy watching intently, taking notes, looking for the kid who will come back into the gym after the minute drill has made him ill, a man among all the boys.