Gay Talese Reminisces About Verrazano Construction

By JOSEPH BERGERJULY 1, 2014

Inside

Photo

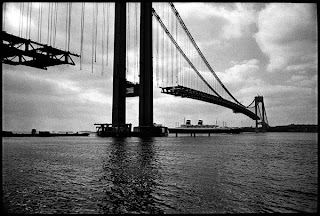

In his coverage of the Verrazano Bridge, Gay Talese wrote about the daredevils who riveted and bolted the steel segments that made up the bridge; its designer, Othmar H. Ammann; and the homeowners displaced by the bridge's path. Credit Image by Damon Winter/The New York Times

Related Coverage

That bridge, the Verrazano-Narrows — the last major bridge built in the New York area before work began last year on a replacement for the Tappan Zee — is 50 years old this year. Already the United States Postal Service has issued a $5.60 priority mail stamp commemorating the opening of the bridge, at the time the world's longest suspension bridge. The Metropolitan Transportation Authority, the bridge's owner, is planning celebratory events but has not worked out details.

The writer Gay Talese chronicled the building of the Verrazano Bridge for The New York Times. Over five years, he produced a dozen articles on the rough-hewn high-altitude daredevils who riveted and bolted the steel segments that made up the two-mile bridge; its austere, brilliant designer, Othmar H. Ammann; and the hundreds of homeowners displaced by the bridge's path. He eventually wrote a book, "The Bridge," which has been republished by Bloomsbury Press, with a new afterword to catch readers up on the lives of those he profiled.

Photo

Sections of roadway were taken out by barge and lifted onto the bridge in sections. Credit Image by Barton Silverman

It is, after all, a very important bridge. It is responsible for turning Staten Island from a lightly populated, largely rural borough connected to the rest of the city by ferry into a place whose population is approaching 475,000, bigger than Atlanta or Kansas City, Mo. It is also a gateway to the city, among the first landmarks travelers by ship see as they enter New York's waters, and the starting line of the New York City Marathon.

Mr. Talese recently compared notes with a reporter chronicling the new Tappan Zee in the writing studio (the cellar) of his East Side townhouse. Mr. Talese, imperially slim at 82, was elegantly outfitted in a Brioni double-breasted blazer with the flourish of a crimson pocket square and shoes handmade by Vincent & Edgar on Lexington Avenue. He has had a fascination with the design and construction of things since his childhood in Ocean City, N.J., where his father, Joseph, an immigrant tailor from Calabria, sewed and shaped finely cut suits by hand.

"Tailoring is construction," he said. "You're dealing with stitches rather than cables. You're dealing with precision. Mr. Amman measured the bridge so that the Brooklyn tower and Staten Island tower are somewhat different in their placement because the curvature of the Earth affected how they would be placed. They had to be measured precisely like a suit. Things that last are well engineered."

Wearing the old hard hat he still keeps, Mr. Talese recalled walking the two-mile-long catwalk of the Verrazano, holding on by a steel rope "banister." A team of workers took him more than once to the top of one of the towers, where "large ocean liners looked like toy boats." He was not there when an ironworker, Gerard McKee, fell off the bridge, but he interviewed Edward Iannielli, who was much lighter than Mr. McKee and had tried to pull him up as he dangled from a catwalk's edge.

He hung around with ironworkers in the bars in Brooklyn, including one, the Wigwam, where the coterie of Mohawk Indians socialized, one of whom wanted to demonstrate his hospitality by offering to let him sleep with his sister.

Photo

Steel cables laid to form one of four suspension cables. Credit Image by Barton Silverman

"Some of the perks of being reporter are surprisingly presented to you when you least expect them," he said with a smile.

The suspension bridge whose construction he depicted cost $320 million to build in 1964 dollars. The three-mile replacement for the Tappan Zee — a cantilever-style architecture — is expected to cost $3.9 billion. Call it a paradox, but its toll is expected to be much lower than the Verrazano when it is completed in 2018. Though the amount has not yet been determined, crossing the current Tappan Zee costs $5, compared with $15 for the Verrazano.

As a reporter, Mr. Talese, who has written profiles of Frank Sinatra and Joe DiMaggio as well as books on such subjects as The Times and America's sexual evolution, has his eccentricities. Practically from the time he started working for The Times in 1953 as a copy boy and wrote his first story on the man who operated the Times Square headline "zipper," he spurned the standard reporter's spiral notebook for slim sections of cut-up white cardboard used by laundries to stiffen the packing of shirts. These days, working in jacket and tie even at home, he writes his articles in longhand, then types them up on his a 1980s-era IBM Wheelwriter 3 typewriter.

As a reporter, he said, "my instinct was to stay away from the big story."

"Do the small story," he said, "and it's not small if you do it well."

A Selection of Articles by Gay Talese

Mr. Talese chronicled the building of the Verrazano-Narrows Bridge for The New York Times.

- Nov. 22, 1964

Verrazano Bridge Opened to Traffic - Nov. 21, 1964

Staten Island Link to Sister Boroughs Is Opening Today - Nov. 15, 1964

Beauty Suspended - Aug. 25, 1964

Tough Bridge Builder Nears End of a Tough Job - June 19, 1964

Anger Lingering as Bridge Goes Up - Jan. 23, 1964

Bridge Delights 'Seaside Supers' - Jan. 1, 1959

Bay Ridge Seethes Over Bridge Plan

In seeing the bridge rise from when it was "a vision on the scratch paper of Mr. Ammann," he was particularly enamored of the ironworkers he met, especially the subspecies known as boomers. These were men, he wrote in the book, who streamed in from around the country in big cars to work on skyscraper, dam or bridge projects in the newest "boomtown," drink to excess and "chase women they will soon forget."

"These guys who put the rivets, they die but their work remains in place," he said. "There's no monument to these people."

Mr. Talese's last article about the bridge was of the opening ceremony. He described, with wry amusement, the procession of official limousines "that moved as slowly as a funeral procession" toward and across the bridge, with Robert Moses, the master public builder whose agency built the Verrazano, in the first car "wearing his battered gray fedora," Gov. Nelson A. Rockefeller and Mayor Robert F. Wagner in following cars, and Mr. Ammann, the great bridge designer of his age, in the 18th car. (Mr. Talese counted the cars. This is, after all, a reporter who found out that the two 695-foot towers were one and five-eighths inches farther apart at their summit than at their bases because of the Earth's curvature.)

In updating his book, Mr. Talese interviewed Joe Spratt, a 29-year-old construction worker who helped put up the antenna that topped off 1 World Trade Center at 104 stories.

"He talked about his father and grandfather and told me that when he was on the top, 'I look around and as I look south I see the towers of the Verrazano and I remember my grandfather Gene Spratt built the bridge.

" 'And if I turn north I see the Penn Central Building across from Madison Square Garden. That's my dad's building.' "

Mr. Talese added: "That's true of all these guys. They look around and everyone sees the skyline of New York as a family tree."

No comments:

Post a Comment